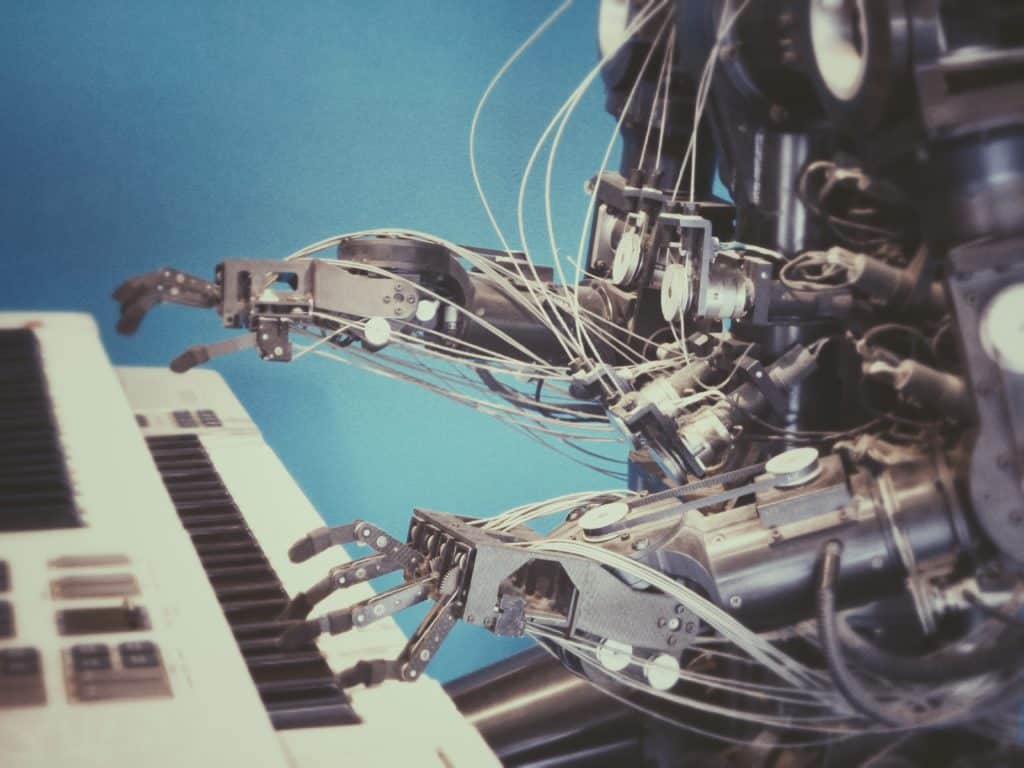

Listen to many futurists, and you would think that robotic engineering and mental health will be the only jobs left in ten years. There’s plenty of reason to pay attention to the massive disruption from the automation of work. But if you’ve ever attempted to do a virtual chat session with a customer service robot or talked to a voice-activated receptionist, you know there’s still plenty of work left for humans.

CNN medical correspondent and neurosurgeon Sanjay Gupta says the human brain can perform in a way that no computer ever will. In his new book Keep Sharp, he writes, “No matter how sophisticated artificial intelligence becomes, there will always be some things the human brain can do that no computer can.”

But just having a brain isn’t enough. It’s using the power of this small, mighty organ to do what technology can’t do nearly as well—adapt and create.

Joseph Aoun, president of Northeastern University, says students need to be prepared to work alongside smart machines. Rather than taking a dystopian view of a world overrun by robots, Aoun argues that humans should focus on what we alone can do—exercise our cognitive abilities to invest, discover, and create something valuable to society. And in his view, this comes down to developing human literacy—flexible thinking, creativity, and cultural agility. In other words, cultural intelligence (CQ).

AI is notoriously bad at adapting to change. Cheaper processing and the availability of data have certainly improved technology’s flexibility to address myriad problems that arise. But AI lacks the human agility to address unforeseen contexts and circumstances. A culturally intelligent individual, however, can take what’s learned from one context and apply it to another. We have the ability to build relationships, work together, create artistic masterpieces, and come up with cures for devastating diseases. Cultural intelligence allows us to leverage the superpowers of the human brain. There will be plenty of work left for us to do in the world of automation. But it’s going to require unlearning how we work and relearning new ways.

Here are a few examples of how CQ allows us to compete with robots:

One of the critical skills needed in a world characterized by robots and increased diversity is the ability to accurately read people. If you can read people, you have a secret power that will not only mean great things for your career but broaden your friendships and networks. Pretty much any job involves reading peoples’ cues and figuring out how to respond. Teachers’ ability to understand a student, graphic designers’ grasp of a client’s wishes and nurses’ conversations with patients are all affected by how accurately they read people.

This is the kind of skill that Qatar Airways has prioritized in training their cabin crew. They recognize that luxury equipment and products don’t set them apart from Emirates or Singapore Airlines. It’s the ability to provide five-star service from a crew who can read their customers and serve them with a personal touch that will truly set them apart.

Understanding cultural values is one of the best ways to get better at reading people. It’s less important to memorize which groups have which cultural value preferences. Someone’s behavior, particularly in the work environment, maybe more strongly shaped by their organizational culture or role than their ethnic or national identity. Instead, look for cues that indicate their value preferences and respond accordingly.

People are reading you just as much as you’re reading them. First impressions emerge within the first seven seconds of meeting. In fact, one study found that we only have a millisecond before people size up whether we’re trustworthy.

Articles across the web repeatedly tell us the behaviors we need to make a good first impression, including how to dress, the kind of handshake to use, and what kind of informal conversation is appropriate. But these tips are biased toward certain contexts. The first time I showed up at Google with a tie on, my host said, “You need to take that off unless you want it to be cut off and added to our wall of shame.” But when I walked into Qatar Airways on a Saturday afternoon to set up for an upcoming training, I quickly observed that I was the only one in the building not wearing a suit, including others who were carrying boxes and moving tables with me. Far too much advice about professional etiquette assumes one-size-fits-all.

Or what about small talk? One of the most significant ways we create the first impression is the communication that occurs informally when we meet someone. International students tell me that the most intimidating part of a job interview is the unscripted portion. What do you say when you’re sitting at the table waiting for the interview to start? What about when your host walks you to the elevator or has lunch with you? They’re right to be concerned. A job candidate’s likability and trustworthiness may be judged far more based on how they behave informally than during the formal interview. It’s not fair. Robots aren’t judged for their likability and trustworthiness, but we are. CQ will help you present the best version of yourself for a diversity of audiences.

Like what you’re reading? Sign-up for our monthly newsletter here.

One more example of how CQ helps us compete with robots is problem-solving. I’ve always been relentless with my teams about never presenting a problem without also suggesting a solution. But problem-solving might be over-rated. Algorithms and sophisticated technology have become very good at analyzing problems and creating solutions more efficiently and accurately than humans do. And even if you don’t have a robot at your disposal, the Internet is full of information about how to solve everything from using Excel to having a difficult conversation with your boss. But where CQ is needed is in finding what the problem is in the first place, particularly if it’s a problem that hasn’t happened before and can’t be identified by running an automated diagnostic.

We don’t have to look far to find corporate examples of failed problem-finding. Best Buy and Walmart’s failures in Western Europe stemmed from an assumption that the market wanted big box stores. Kodak, Blockbuster, Blackberry, and Nokia misread technological trends and needs.

Unclear solutions begin as unclear problems. The ability to identify problems and come up with innovative solutions is the secret to any good business. And it’s at the core of good medicine, education, engineering, and more. The 21st Century workforce needs culturally intelligent humans who are adept at problem-finding for a diversity of people and contexts. The skills we develop to read people are the same ones we exercise to find problems—slowing down, using perspective-taking, questioning assumptions, and understanding the invisible values that shape behavior.

Darwin’s 19th Century words are relevant for how we compete with robots: “It’s not the strongest that survives, not the most intelligent. It’s the one that is most adaptable to change.” If the last year has taught us anything, it’s that adaptability is critical. CQ not only makes you more competitive in the job market, but it also gives you the skills to adjust to the constantly shifting world surrounding us. Employers and universities know it. Robots know it. But do your priorities show that you know it?

[Adapted excerpt from David Livermore’s next book, due to release in 2022].

David Livermore, Ph.D., is a social scientist devoted to the topics of cultural intelligence (CQ) and global leadership and the author of 12 award-winning books. His best-selling book Leading with Cultural Intelligence is being used widely across the world and his book, Driven by Difference, was featured in The Economist as a fresh, much-needed approach to DEI. He leads the Cultural Intelligence Center in East Lansing, Michigan, and he’s a visiting research fellow at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. Before leading the Cultural Intelligence Center, Dave spent 20 years in leadership positions with various non-profit organizations around the world and taught in universities. He’s a frequent speaker and adviser to leaders in Fortune 500’s, non-profits, and governments and has worked in more than 100 countries across the Americas, Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe.

The Cultural Intelligence Center is an innovative, research-based consulting and training organization that draws upon empirical findings to help executives, companies, universities, and government organizations assess and improve cultural intelligence (CQ) – the ability to work effectively with people from different nationalities, ethnicities, age groups, and more. We provide you with innovative solutions that improve multicultural performance based on rigorous academic research. More information about the Cultural Intelligence Center can be found on our website located at http://www.CulturalQ.com.

Stay Connected

Follow Us on LinkedIn | Subscribe to our Newsletter | Contact Us